The Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation (VOC) is well known, but its origins are not. This notorious right-wing organization is the successor to the National Captive Nations Committee (NCNC), a relatively obscure outfit that created the VOC in the 1990s and faded into its shadow by the 2000s.

In other words, the hidden history of the “Victims of Communism” starts no later than 1959-60 with the creation of “Captive Nations Week” and the NCNC. Over the next month we’ll take a broader look at the “Captive Nations Lobby” to see how the VOC absorbed the mantle of an extreme Cold Warrior movement—the revival of which appears to be on its agenda.

In a previous installment of VOC INFO, readers met “Mr. Captive Nations,” Lev Dobriansky, the lifetime chairman of the National Captive Nations Committee, the longtime president of the Ukrainian Congress Committee of America (UCCA), and arguably the chief founder of the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation. During the Cold War, Dobriansky became an ally of the far-right OUN-B, or “Banderite” faction of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, which had tried to implement a genocidal partnership with Nazi Germany to create a nominally independent, fascist “Ukraine for Ukrainians.”

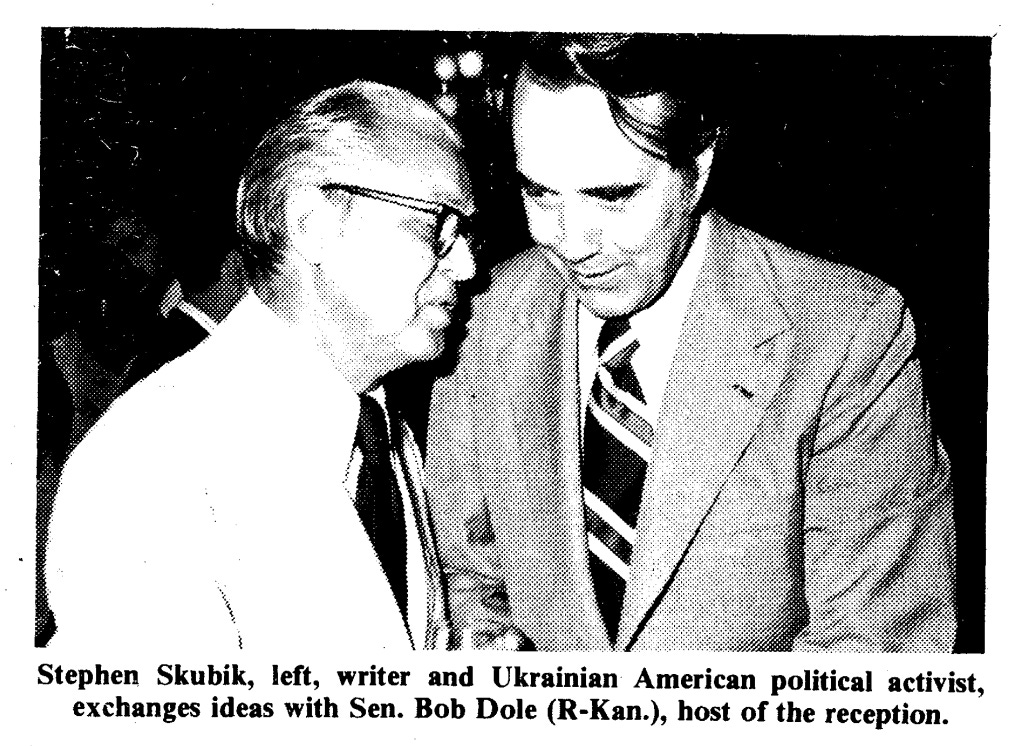

Lev Dobriansky organized the NCNC to oversee “Captive Nations Week,” which he basically invented, but more about this Week next week. Dobriansky presumably recruited the NCNC’s first treasurer and secretary: Stephen Skubik, a Ukrainian American veteran of the U.S. Army’s Counter-Intelligence Corps, and a fellow member of the UCCA, the All-American Conference to Combat Communism (AACCC), and the GOP’s “Nationalities Advisory Committee.”

As told by his obituary, Stephen J. Skubik (1916-1996) “started life in a basket left on the doorstep of a Ukrainian church in Philadelphia,” and in his Depression-era teens, “spent a year traveling across the country as a railway hobo.” By 1970, he “suggested the concept of building a monument to the victims of Communism” according to Donald Miller, the executive director of the NCNC and the Korean Cultural and Freedom Foundation, which was a front for the Moonie cult, or Unification Church. Skubik and Miller served on the “American Action Committee” of the AACCC, which announced “Operation M” to create a memorial for the “victims of communism.”1

Donald Miller, a retired Naval intelligence officer and former editor of the AACCC publication “Freedom Facts,” predicted, “Operation ‘M’ will conclude with [the] unveiling and dedication of the memorial in 1976,” to coincide with the bicentennial of U.S. independence. This didn’t occur, but Miller did later in life become a trustee of the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, which one could say belatedly accomplished “Operation M” in 2007.

In 1993, the year that Congress “encouraged” the NCNC to “create an independent entity” for its victims of communism memorial project, a 77-year old Stephen Skubik self-published a poorly written, dubious and conspiratorial book, “The Murder of General Patton,” according to which the author had a life changing meeting with OUN-B leader Stepan Bandera, the infamous Ukrainian Nazi collaborator, just a week after World War II ended in Europe.

US general George Patton, who openly resisted the de-Nazification of postwar Germany, died soon after a car accident left him paralyzed from the neck down in December 1945. According to an admirer of Patton who researched his demise, “nobody seriously discussed that a conspiracy lay behind his death” until a 1978 Hollywood film (Brass Target) imagined that corrupt U.S. officers staged the accident and broke his neck with a rubber bullet.

Stephen J. Skubik didn’t hop on the bandwagon, or at least not for another 15 years, and with a twist: it was actually the Soviets that murdered Patton “in collusion with the American OSS (Office of Strategic Services),” the forerunner to the CIA. Then the KGB assassinated Bandera in 1959, “because he knew who killed Patton.”

“The Russian NKVD and their American OSS friends were furious with me,” Skubik recalled in 1993. “They said I was an UPA agent, working for Bandera.” Supposedly he had feared for his life to tell the story, but now it was coming to an end. Skubik’s son eventually posted a copy online with a note to readers: “All of the events described in the book are the war stories we grew up with. My dad was utterly consistent over the years with the ‘facts’ that are represented in his book. That said, the book is not well documented from an academic perspective. The reader should bring a skeptical eye to the story.” So it went,

the Offices of Strategic Services, under General William Donovan, was dealing with the Soviet NKVD and KGB for intelligence cooperation and exchange. The Soviets had willingly agreed to place NKVD agents into the OSS. There were NKVD agents in many sensitive positions in Washington, D.C. at Treasury, at State Department and even at the White House. The military intelligence in the field was penetrated by the NKVD. General Donovan’s agreement to recruit NKVD agents was made with the hope that there would be a harmonious and friendly relationship between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. Patton’s belligerency caused Donovan no end of difficulty. The OSS in the field and in Washington were informed by the NKVD that Patton was making cooperation very difficult.

When I continued to report to the OSS about the threat against Patton’s life, I had no way of knowing that I was letting the NKVD know that the Ukrainian intelligence people were knowledgeable of the NKVD order to kill Patton… The Ukrainians, especially the Bandera people, were quite upset that the U.S. intelligence people weren’t willing to listen to them. I told my Ukrainian contacts that I would be leaving Germany in early January [1946] and that I might be able to tell their story in Washington. When I got to Washington, I spoke to my girlfriend who worked with the Army Security Agency. She suggested that I let the matter drop since it could not be proved. I took her advice and I’m glad I did since I probably wouldn’t be alive to write this story.

Skubik tells us that he was part of Patton’s Third Army, and as a CIC Special Agent with the 89th Infantry Division, “I caught 6 spies, 17 Gestapo Agents, a number of Nazi Kreisleiters and Gauleiters.” After the war, he was initially based in the city of Zwickau, which was slated to become part of the Russian zone of occupied Germany according to the Yalta agreements. Skubik wrote that before evacuating with other U.S. forces, he packed a freight train with “car loads of gold paints, ceramic kilns and supplies, factory machines, tooling machines, and thousands of gallons of German wines.”

This of course infuriated the Russians. I could care less how angry they were. I had nothing but trouble with the Russians and their German communist minions… I suppose the worst thing I did to the soviets, up to that time, was to take arrested communist leader Ulbricht with me as I headed to the new American zone.

Skubik claimed that he arrested future East German leader Walter Ulbricht and, with his partner taking the lead, they staged a mock execution in the woods. Ulbricht, he later imagined, “was one of ‘Wild Bill’ Donovan’s recruits. No wonder my name was mud with the OSS General.”

About ten kilometers out of Zwickau, Harry asked me to stop the jeep. I did, and asked why. He said, “I want to show this son-of-bitchin’ communist what fear means, I want to give him some of his own medicine.” I asked him what he was going to do. He told me that he wanted to take Ulbricht into the woods and shoot the bastard. I looked at Ulbricht, he understood what Harry wanted to do. I suggested to Harry that he take him into the woods, but that I wanted no part of murder. Harry laughed, he put his forty five to the guys head and pulled the trigger. Harry laughed and said, “Damn it, must have been a bad bullet.” He fired again, this time Ulbricht collapsed.

Is this according to his imagination? Days after the Nazis surrendered, Skubik allegedly went to Czechoslovakia “with a German SS Corporal and an SS Secretary/Stenographer,” named Hans and Marta, who “had been at the last meeting of hundreds of escaping Nazi bigwigs.” Supposedly the pair led him to the spot where lists of the “bigwig” names and their destinations were buried.

Skubik said they had a run-in with Soviet soldiers, who received orders “to escort me to Prague to talk with the Commanding General.” Instead, the CIC special agent panicked, and made a daring escape with his Nazi informants, after which “we laughed and cheered and even gave an Indian yell.” Skubik recalled speeding off with “my machine gun ready to fire” on Soviet allies—three days after they triumphed over Nazi Germany, and five days before he paid a visit to Stepan Bandera in Munich.

The only detail that Skubik shared from his meeting with Bandera was that the OUN-B leader told him Josef Stalin ordered the assassination of George Patton. Skubik said that he relayed Bandera’s warning to one “Major Stone” in the OSS, who already heard this rumor, and advised, “Stay away from Bandera. He’s bad news.” Later on, Skubik alleged that he also spoke to OSS chief William J. Donovan about this: “He told me that Bandera was on the list to be arrested. That his rumor about Patton was a provocation. He ordered me to arrest Bandera. (Which I couldn’t do without killing twenty or more of his body guards.)”

Stephen Skubik wrote that he subsequently questioned other Ukrainian nationalist leaders, who repeated the rumor about Patton. Skubik “interrogated” General Pavlo Shandruk, who had commanded the remainder of the Ukrainian Waffen-SS division, and Professor Roman Smal-Stocki, who was also wanted by the Soviets as a Nazi collaborator.2

“Steve, the Ukrainians are trying to use you to get us mad at the Russians,” said a fellow CIC agent. “There was a very sinister anti-Ukrainian bias in the intelligence community,” according to Skubik. “It appears that even being a friend of Ukrainians was dangerous.”

He allegedly got in trouble with the OSS director again for trying to give him four volumes of notebooks from Shandruk. This is how Stephen Skubik described “Wild Bill” Donovan, the founding father of the Central Intelligence Agency.

There I was once again with that angry S.O.B. who believed all Ukrainians were Nazi collaborators, anti-Semitic and trying to cause a war with Russia. He believed I was an UPA agent. “Soldier, what kind of crap is this you’re bringing me? Why did General Shandruk ask you to deliver this to me? … Take this stuff to the British. They're dumb enough to believe the Ukrainians.”3

When he heard about Patton’s accident on December 9, 1945, Stephen Skubik was sure, “the NKVD finally did it.” The car crash was almost perfectly staged, because Patton was the only one injured, but in fact he survived. “It had to be Soviet NKVD agents or their OSS communist agents who killed him at the hospital in Heidelberg.”

Skubik wanted to investigate, however received strict orders: “Stay the hell out.” So he turned to his Ukrainian sources for more information. Apparently he spent Christmas Eve with Professor Smal-Stocki and General Shandruk, and soon thereafter was honorably discharged. Skubik and Smal-Stocki were eventually reunited in the UCCA and the National Captive Nations Committee.

At some point, back in Washington and taking a stroll in front of the White House, Skubik claimed that he had a chance encounter with “OSS Major Stone,” who cautioned him against accepting an offer to join the forerunner to the CIA Office of Special Operations. “Don’t do it, they want you back in uniform in order to kill you,” Skubik said he said. “Because you are political dynamite. You’ve got the Russians mad as hell… Steve, go underground for a few years.”

So the story goes, “I felt free to roam the streets in Washington after Ohio Senator Robert Taft recruited me to work at the Republican National Committee in 1951.” This part could actually be true. For starters, the sponsor of the infamous Taft–Hartley Act was the only presidential hopeful who fully embraced the extremist goal of “liberating” the “captive nations.”

That year, Skubik joined the executive committee of the right-wing All-American Conference to Combat Communism, which counted Lev Dobriansky’s Ukrainian Congress Committee among its major affiliates. Meanwhile, the RNC created an Ethnic Origins Division, which soon enough published a pamphlet by Skubik: “Republican Policy of Liberation or Democratic Policy of Containment.”

Historian Robert Szymczak explains that it was for the 1952 presidential election campaign that “the Republican Party mounted, for the first time in its history, a concerted effort to attract the ‘ethnic vote,’ specifically those voters of Eastern European background who had for decades supported the Democrats.”

GOP strategists knew they had an emotional issue in the fate of the Eastern European nations under Soviet control since the end of World War II. They immediately made plans to concentrate on the policy of Liberation, as opposed to Containment, which was characterized by John Foster Dulles, the Republican National Committee’s foreign affairs advisor, as the abandonment of 800 million people to “godless Communism” and a perfect example of “non-moral policy.”

… The party strategists believed that a resounding repudiation of Yalta and all its implications could be achieved at the polls with the help of the ethnic vote… Eisenhower, however, was never comfortable with either the liberation policy or the repudiation of Yalta.

… The Democratic Presidential candidate, Adlai E. Stevenson, began to condemn the liberation policy as a “cynical and transparent attempt, drenched in crocodile tears, to play upon the anxieties of foreign nationality groups in this country.” President Truman angrily accused the Republicans of “… playing a cruel, gutter political game with the lives of countless good men and women behind the iron curtain … nothing could be worse than to raise false hopes … that can only end by giving a new crop of victims of the Soviet executioners.”

Szymczak suggests that the architect of the 1952 “Policy of Liberation” wasn’t (just) Dulles, the next Secretary of State and brother to Eisenhower’s CIA director, but Arthur Bliss Lane, a former US ambassador to Poland who “shift[ed] to the far-right” after he resigned in 1947 and wrote a book, I Saw Poland Betrayed. Lane directed “Foreign Language Groups Activities” within the RNC’s Ethnic Origins Division. He also sat on the board of the National Committee for a Free Europe, a major CIA front, which later sponsored the Assembly of Captive European Nations, an important facet of the “Captive Nations Lobby.”

Stephen Skubik recalled in 1993, “I was kicked off the Eisenhower campaign team, but not before I had a chance to convince John Foster Dulles to adopt the Policy of Liberation which I had written for Taft.” This fabulous claim may yet contain a kernel of truth. Szymczak writes that Lane’s “chief ally was John Foster Dulles, the GOP foreign policy advisor. Lane and Dulles had conferred on numerous occasions on the idea of a condemnation of Yalta.” Maybe Skubik was in the room for one or more of these discussions? In Szymczak’s essay, “Hopes and Promises: Arthur Bliss Lane, the Republican Party, and the Slavic-American Vote, 1952,” which I’ve been quoting from, there is a footnote citing a letter from Lane to “S.J. Skubik” dated January 23, 1952.

The Ukrainian Congress Committee sent Stephen J. Skubik, future VOC founder Lev Dobriansky, and three other representatives to the 1952 Republican national convention, where they urged the platform committee to adopt a foreign policy plank “advocating and supporting freedom and independence for all nations enslaved by Soviet Russia.”

The GOP pledged to “repudiate” the Yalta agreements and “the negative, futile and immoral policy of ‘containment’ which abandons countless human beings to a despotism and godless terrorism,” but as Robert Szymczak tells us, “liberation” was just a Republican carrot for imagined voting blocks.

What became of the Republican “liberation of Eastern Europe” doctrine and the repudiation of the Yalta accords the party dangled in front of American voters of Eastern European ancestry? Precious little, to be sure, resulted from the emotional, often bombastic rhetoric, drenched in Cold War terms calculated to appeal to the ethnics’ concern for ancestral lands. Lane, for one, never abandoned his belief in liberation and the abrogation of Yalta, but after Eisenhower’s inauguration, the new administration simply let both matters drop, much to the relief of the State Department and our European allies…

The advocates of liberation created the dangerous illusion that the United States was omnipotent; earlier failures had invariably been caused by conspiracies and betrayals… In the end, the liberation policy showed itself for what it was during the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, when Budapest’s frantic appeals for assistance went unheeded as Soviet tanks crushed the resistance: an empty promise made, despite the sincerity of some of its proponents, in order to win votes.

The Eisenhower administration’s abandonment of “liberation” hardened the emerging “Captive Nations Lobby,” which made friends with some of the most fanatical Cold Warriors in Congress and across the world. Stephen Skubik became the first secretary and treasurer of the National Captive Nations Committee, but more importantly, a longtime consultant to the RNC.

By the mid-1960s, Skubik had attended an “American Nationalities for Nixon-Lodge” meeting at the White House, served as executive director of the Nationalities Division of the RNC (and apparently begun to suspect that the Soviets killed one of its Ukrainian leaders in the New York City subway), become the vice-chairman of the UCCA branch in Washington DC, and joined the latter’s committee for the construction of a monument in the US capital to honor Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko. Readers of “Mr. Captive Nations vs. the CIA” may recall that drama related to unveiling this memorial allegedly pushed Lev Dobriansky over the edge and into the arms of the Banderites.

By the early 1970s, Skubik was the secretary of the Ukrainian Catholic Studies Foundation chaired by Dobriansky, and became the finance chairman of the Republican Heritage Groups Council, which journalist Russ Bellant described as the RNC’s “special ethnic outreach unit.” In his 1989 book, Old Nazis, New Right & the Republican Party, he demonstrated that “antidemocratic and racialist components of the Republican Heritage Groups Council use[d] anticommunist sentiments as a cover for their views while they operate[d] as a de facto emigré fascist network within the Republican Party.” As we shall see in this VOC INFO series, there are stronger connections to be made between the “Heritage Groups Council” and the NCNC as well as the “Victims of Communism.”

By the 1980s, Skubik was in his 60s, and living in New Hampshire, where he retired. It was in the 1990s that he wrote “The Murder of General Patton,” and died from cancer. Skubik’s long and detailed obituary in the Ukrainian Weekly newspaper sounds like he wrote it himself. It credited Skubik with numerous feats, such as being “the first U.S. intelligence officer to enter and report first-hand on the Nazi death camps,” uncovering “a Soviet assassination plot against Gen. George Patton,” authoring the GOP’s “Liberation Policy platform” in 1952, working on eight presidential campaigns (“from Robert Taft in 1952 to Ronald Reagan in 1980”), and arranging a meeting after World War II that “led Gen. Eisenhower and the U.S. State Department to reverse U.S. policy on [repatriating] Soviet refugees.”

“The Murder of General Patton” apparently inspired a decade of far-fetched research by Robert Wilcox, the author of “Target Patton: The Plot to Assassinate General George S. Patton.” Taking Skubik seriously, this book hit the shelves in 2014 thanks to Regnery Publishing, a conservative leader in its field. (The founder, Henry Regnery, was an original member of the NCNC, and his son Alfred is a former trustee of VOC.) Skubik and Wilcox subsequently became part of Bill O’Reilly’s “Killing Patton,” another conspiratorial book from 2014.

A few years ago, Victor Rud, a leader of the Ukrainian American Bar Association who chairs its Committee on Foreign Affairs and has written articles for the influential Atlantic Council and CEPA think tanks, referenced Skubik’s conspiracy theory in an op-ed: “it was the Ukrainian underground that warned our Office of Strategic Services of Stalin’s plan to assassinate General George C. Patton… Washington then turned on the Ukrainian informants, tipping off NKVD Maj. General Davidov…” This was supposedly the Soviet general that Skubik confronted about a plot to kill Patton—the man who “cost me my rank and almost cost me my life.”

In another alleged encounter, Stephen Skubik had the nerve to tell Soviet soldiers in occupied Germany, who just defeated Hitler’s Third Reich after tens of millions of their people died, “It seems to me that you communists are no different than the Nazis.” At the end of the day, this hateful turd was just one of many that floated upwards in the Washington swamp, which for decades has been “drenched in crocodile tears” by self-appointed spokespeople for the “captive nations” and “victims of communism.”

STAY TUNED FOR MORE COMING SOON ON THE ‘CAPTIVE NATIONS LOBBY’ AND THE VICTIMS OF COMMUNISM MEMORIAL FOUNDATION ☭☭☭

Another member of the AACCC American Action Committee was Karol Sitko, later described by journalist Russ Bellant as the leader of a “subsidiary of the pro-Nazi German American National Congress… [and] also the organizer for the West German branch of the Western Goals Foundation, a far-right political organizing and research group which, until the death of its founder, Congressman Larry McDonald, was essentially a front for the John Birch Society's private intelligence network.” As of 1973, Sitko was the director of public relations for the American Friends of the Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations, a far-right pillar of the “Captive Nations Lobby.”

Shandruk and Smal-Stocki were leaders of the Promethean League, which aspired to foment rebellion among the non-Russian peoples of the Soviet Union, and appears to have been folded into the more extreme Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations (ABN) led by the Bandera cult. More about this another day.

In fact the British did support the Banderites and ABN, at least in the early years of the Cold War. The CIA convinced them to put a stop to this in the 1950s, but it was too late. We’ll be coming back to the ABN in another installment of this series.