If the previous installment of this Captive Nations Week VOC INFO series was about the American Friends of the Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations, this one is about its CIA-funded rival, the Assembly of Captive European Nations (ACEN), which was established in 1954.

Many reading this will already know about the National Committee for a Free Europe, also known as the Free Europe Committee, the major CIA front organization that oversaw the ACEN, because it created Radio Free Europe. There was also the Crusade for Freedom, the domestic “fund-raising arm” that provided cover for the CIA to finance this entire apparatus. According to Blowback: America’s Recruitment of Nazis and Its Effects on the Cold War by Christopher Simpson,

Through the National Committee for a Free Europe (NCFE) and a new CIA-financed group, the Crusade for Freedom (CFF), the covert operations division of the agency became instrumental in introducing into the American political mainstream many of the right-wing extremist émigré politicians’ plans to “liberate” Eastern Europe and to “roll back communism.”

In other words, the CIA largely planted the seeds of the “Captive Nations Lobby,” which sprouted in the 1950s. The ACEN essentially functioned as a Model United Nations club for the following members, and aspiring governments in exile: the National Committee for a Free Albania, the Bulgarian National Committee, the Council of Free Czechoslovakia, the Committee for a Free Estonia, the Hungarian National Council, the Committee for a Free Latvia, the Committee for a Free Lithuania, two Polish organizations, and the Romanian National Committee. According to historian Anna Mazurkiewicz,

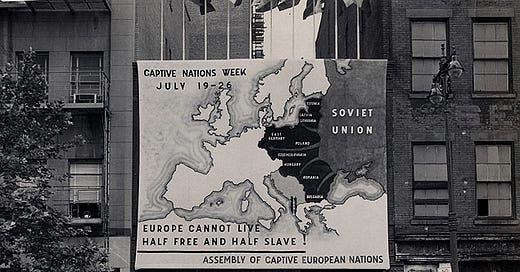

the ACEN wished to be perceived as an alternative to the communist representation of East Central European nations in the free world – a “little UN”– as the “New York Times” referred to it at one point. In 1956, the ACEN received some funds to organize the Captive Nations Center across from the UN Building. The money was not enough to open the actual center, but the façade of the rented building was used to display political posters directly opposite from the UN headquarters. Together with the Carnegie International Center, located just around the corner, these locations where the ACEN delegates met offered prestige and the opportunity to be noticed by the UN representatives, diplomats, journalists as well as any potential visitors and tourists. In the years 1954 to 1972, the ACEN held 18 sessions. The ACEN’s Plenary Meetings were organized in concurrence with the UN sessions and therefore they began in September.

The CIA once described the ACEN as “a propaganda organization and a lobby.” VOC advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski told Anna Mazurkiewicz, “I believe the initial purpose of the ACEN was to provide political legitimacy for sustaining from outside the internal opposition to communism.” The Assembly was not packed to the gills with former Nazi collaborators like the ABN, but then again, according to Christopher Simpson, “The Albanian [Nazi] collaborationist Balli Kombetar organization controlled the pivotal ACEN Political Committee for most of the 1950s.” Hasan Dosti, the former minister of justice in Italian-controlled Fascist Albania, led the Free Albania Committee, and chaired the Albanian delegation (which included several Balli Kombetar leaders) at the first session of the Assembly of Captive European Nations. Simpson tells us,

It would be a mistake, however, to view the ACEN as a whole as a “Nazi” organization. The influential Czech delegation was controlled by anti-Nazi (and anti-Communist) moderate socialists. The Polish delegation consisted in large part of the old wartime Polish government-in-exile in London combined with a handful of surviving Polish underground fighters, many of whom had risked their lives in the struggle against Germany. Most of the Hungarian emissaries were indisputably conservative but apparently free of culpability for war crimes, and so on. The relatively mainstream character of those ACEN groups, including the anti-Communist and anti-Nazi credentials of some top ACEN leaders, gave this Captive Nations movement a thoroughly acceptable image in the eyes of the media and the public at large.

Niko Nakashidze, the Georgian prince and former Nazi collaborator that we heard from in the previous installment, complained that members of the ACEN “consist of leftist exile politicians.” The ACEN’s Bulgarian National Committee, Council of Free Czechoslovakia, and Hungarian National Council were rivaled by their fascist counterparts in the ABN, including the “Slovak Liberation Committee” chaired by Ferdinand Durcansky, a wanted Nazi war criminal, and the “Hungarian Liberation Movement” led by General Ferenc Farkas, who “appears to be the Hungarian neo-Nazi candidate for leadership of the military elements of the emigration,” according to a 1958 CIA study.

“ACEN and ABN membership did not overlap,” according to Anna Mazurkiewicz, with one exception. Before the ACEN was established, one of its Latvian leaders, Alfred Berzins, chaired the “Peoples’ Council” of ABN, making him its second-in-command after Yaroslav Stetsko. In 1952, already on the staff of the CIA’s Free Europe Committee, Berzins unsuccessfully “approached some of the Americans in Free Europe as to the possibility of sponsoring Stetsko to the United States.” As we already know, that was not going to happen, but future VOC co-founder Lev Dobriansky helped the ABN leader get his first US visa in 1958. Once again we can return to Blowback by Christopher Simpson.

Alfreds Berzins, now deceased, was propaganda minister in the prewar Latvian dictatorship of Karlis Ulmanis. During World War II Berzins “help[ed] put people in concentration camps,” according to his CROWCASS wanted report, and was “partially responsible for the deaths of hundreds of Latvians and thousands of Jews.” The United States asserted that Berzins was “responsible for murder, ill treatment and deportation of 2000 persons.” He was, the United States said, “a fanatic Nazi.”

The ACEN stepped up its lobbying efforts after the 1956 Hungarian revolution was crushed. Among other things, it organized the “American Friends of Captive Nations,” which according to Anna Mazurkiewicz described itself as “a liaison between the ACEN and the American public and various anti-Communist organizations… because ACEN cannot carry on educational work among the American people.”

Mazurkiewicz writes that “by 1957, the ACEN’s members had already realized that the U.S. government policy toward Eastern Europe was no longer about the restoration of freedom and democracy but about freezing the status quo and maintaining so-called peaceful coexistence. The ACEN did not agree to go along with this plan. In insisted on a firm ‘no’ to the status quo.” But the Assembly of Captive European Nations faced budget cuts over the coming years, and because it relied on the U.S. government, the organization faded away.

Mazurkiewicz counted 175 meetings that representatives of ACEN had with members of Congress in 1955-1963. According to this historian, “It should be mentioned, however, that during the decade analyzed here, the cases of citing ACEN materials by staunch anti-Communists in the congress were rather sporadic. For them, this organization was not radical enough.” The far-right American Friends of the Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations, on the other hand, was established a couple years before the ACEN, and outlasted it by many more. The next installment of this series will be about the Cold Warriors in Congress who were perhaps the most important part of the “Captive Nations Lobby.”